Afternoon Everyone!

I hope you all well :)

This post is looking at Choking and Yips in Golf. It was an essay I had written back during my undergraduate degree.

These are my own words, feel free to reply below in the comments section.

Looking forward to hearing your replies

|

| Image Credit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wE_zbnnJlsk |

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

**Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for 'fair use' for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favour of fair use**

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1.0

Abstract

The literature reviewed is centred on “yips, choking,

arousal, stress and anxiety” in sport. The sport of focus is golf as it is subjected to all these factors from

grass roots level to the professionals on the PGA Tour. Three journals

will be analysed within this review comparing their methodology, defining

topics, and identifying strengths and limitations between testing procedures

and participants. The findings will be reviewed in order to hypothesise where

future research needs to direct itself. The literature reviewed was analysed

from online databases such as Scopus, Sport Discus and Sage journals. The journals are by the following authors;

Klampfl, Lobinger & Raab (2013), Woodman, Akehurst & Beattie (2010)

and Stinear, Coxon, Fleming, Lim, Prapavessis & Byblow (2006). Reviewing

these papers, there is no standardized method to identifying and/or quantifying

yips affected golfers. More studies can lead to a classification for golfers with

yips which could provide a useful framework for the appropriate management of

yips symptoms.

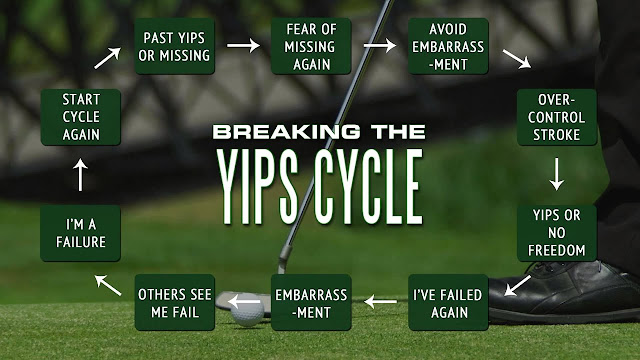

1.1 Background on Yips

and Choking

Klampfl,

Lobinger & Raab (2013), gave

a detailed account on the background of what Yips and Choking is. Yips occur

mostly during the putting component of golf, as it consists of involuntary

movements appearing shortly before hitting the ball that results in a loss

of control which leads to missing the putt (McDaniel, Cummings & Shain

1989; Smith et al 2000; Steiner et al 2006). The yips is well known in golfing

circles and statistics shows it affects 28-48% of all participants (McDaniel et

al 1989; Smith et al 2000). The golfers who stated they were affected by yips identified

that the symptoms (similar to choking) occurred at pressure situations (McDaniel

et al 1989, Philippen, Klampfl & Lobinger, 2012). Yips is associated with choking

under pressure defined as “the process whereby

the individual perceives their resources are insufficient to meet the demands

of the situation and concludes with a significant drop in performance – a

choke” (Hill, Hantin, Fleming and Matthews 2009). Performance anxiety is

theorised that it plays a huge role in setting off the yips (McDainel et al

1989; Smith et al 2000). Yips can be described as a very bad form of choking

(Masters 1992) as it has similar characteristics to it (Bawden and Maynard

2001). It can be argued that beginner golfers with little to no experience,

combined with a high handicap, do suffer from the yips (Philippen, Klampfl

& Lobinger 2012).

Gucciardi

& Longbottom (2010) stated that, yips isn’t acute but is chronic, and

happens over a period of time. This can be exemplified by Rory McIlroy, the

Northern Irish golfer, who was leading the US Masters in 2011, and then had a

catastrophic failure on the last day when he dropped nearly ten shots due to

putting errors (the yips) and choking on the tee when playing high pressure

shots. Many different measurement methods have been used to investigate the

yips including recording muscle activity using electromyography (EMG), grip force,

heart rate, putting performance and kinematic parameters. It has been shown

that yips affected golfers exhibit an increased muscle activity (Smith et al

2000, Steiner et al 2006) within the lower forearm muscles (Alder et al 2005,

2011).

While

this is significant, Smith (2000) found yips affected golfers had decreased

performance accuracy which can be attributed to an increase in anxiety and

elevated arousal levels. Applying the inverted U-Hypothesis; as arousal

increases, so too does performance, were it comes to a point too much arousal

leads to a decrease in performance (Hardy & Fazey 1988). This decrease in

performance can be described as choking or better explained as the Catastrophe

model (Hardy 1990). However, in Steiner’s 2000 paper, there was no recorded

difference in performance between affected and non-affected yip groups on their

accuracy.

2.0 Literature

Review

In this section, the report will look at what theories underpin

choking and yips, and the methodology of the papers analysed.

2.1 Theories

Models which explain the mechanisms of choking

under pressure include Distraction Theories (Eysenck & Calvois 1992) &

Self Focus Theories. Distraction looks at athletes focusing on anything but the

task at hand e.g. a runner would focus on their breathing instead of their

position in the race. Self focus theories assumes that performance anxiety

causes the athlete to shift the focus of attention inward or to consciously

monitor the skill, which detrimentally affects the well learned, automated

action (Baumeister 1984).

The Reinvestment Theory is

defined as the manipulation of conscious explicit, rule based knowledge, by

working memory to control the mechanisms of one’s movements using motor output

(Masters 1992). “To yip or not to yip, that is the question” (Rotherham,

Maynard, Thomas & Bawden 2007), found through a questionnaire, that yips

affected athletes had an increased tendency both to consistently control

(reinvest in) their movements and to be perfectionists. The occurrence of

choking under pressure also depended on two appraisals, according to the class

stress model (Lazarus 1974).

Yips can also be

described as a physical issue. Dystonia (or better known as Focal Dystonia) describes

a neuromuscular movement disorder whose symptoms include involving muscular

contractions resulting in twisting & repetitive movement or abnormal postures

occurring exclusively in one body part and during the performance of a task

(Pont-Sunyer, Martí, & Tolosa 2010). Dystonia has also been reported in table

tennis (Le Floch et al 2010) and tennis (Mayer, Topka, Boose, Horstmann &

Dickhuth 1999). Mechanisms of dystonia are still unclear but are assumed to

involve abnormalities within the basal ganglia, inhibiting & processing

dysfunction of the sensorimotor system & abnormal plasticity (Rosenkaranz

et al 2008).

2.2

Yips in Golf

The

purpose of the first paper, “The Yips in Golf: Multimodal Evidence for Two

Subtypes”, was to determine whether a model of the two subtypes of yips is

supported by evidence from a range of physiological, behavioural and

psychological measures. There were 24 volunteers divided into affected and non-affected

yip groups. Statistical tests used included a one way analyses of variance to

test for the differences between the golfing groups and the independent

two-tailed t-tests were used also. The subjects were measured physically using

an EMG (electromyography) to record muscle activity, performance measure

(putting ability) and psychologically (state anxiety) using the CSAI-2

(Competitive State Anxiety Inventory – 2) scale.

They were tested in

situations to create high/low pressure/monetary incentive to either facilitate

or inhibit the subjects’ putting performance using a video camera to record

them (higher pressure) and/or a confederate to use negative reinforcement when

they missed a putt. Limitations of this paper included putting accuracy was 50%

for all three groups, implying the task may have been quite difficult. The

control group of golfers tended to be younger and of a lower handicap than the

two other yips groups. This is to be expected as yips takes a number of years

to develop to compromise a performance and is consistent with previous research

(McDaniel et al 1989).

The purpose of the study

was achieved as the results supported the classification of yips into Type 1

and Type 2. The four hypothesis for this study concluded that under low

pressure situations, there still is a large amount of muscle activity in the

Type 1 golfers when compared to the control group. Type 2 golfers’ performance

was significantly better in the absence of monetary reward (high pressure). It was confirmed that Type 2 golfers would

have higher state anxiety but this was a small difference and did not affect

low and high pressure situations.

|

| https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-science-of-choking-under-pressure-133896043/ |

2.3 Self

Confidence and Performance

The objective of the

second paper, “Self-confidence and performance: A little self-doubt helps”, was

to test the theory that a decrease in confidence on a well learned task will

increase effort and performance. It used a two (group: control, experimental) x

two (trial: practice, competition) mixed-model with repeated measures on second

factor. The study used expert skippers.

Their confidence was reduced via a combination of factors including changing of

equipment or the environment. The 28 participants who volunteered were all

confident with their skipping ability. Confidentiality was assured. Subjects

were randomly assigned to either a control or an experimental group with a monetary reward in the competition trial. Both used

the same type of skipping rope except the experimental group was coloured white to create self-doubt.

Performance was measured

using how many skips per minute. Measuring tools included the use of the SSCI

(State Sport Confidence Inventory) and an auditory probe in the skipping rope

to record the number of skips. The study used a mixed model analyses of variance

(ANOVA) on performance and showed a significant main effect for the

experimental group. Results from the study supported the initial hypothesis.

Post hoc tests showed a significant decrease in confidence but improvement in

performance, but only in the experimental group. Main limitations of this study

is the simplistic nature of the task as it has

no real carry-over to any sports. If it was applied to more complex tasks such

as golf or pole vault, then it would carry more weight. Also, there was little presence of

competition which would have increased anxiety and arousal levels leading to

the possible occurrence of yips being shown. A positive take from this is most

research states, when confidence is reduced, performance is reduced too

(Woodman & Hardy 2003). However, in this paper, performance was improved.

The literarure surrounding self-confidence, for the majority, leans towards reduced confidence means a decrease in performance

(Feltz 1988).

2.3 How to Detect

Yips in Golf

The purpose of the final paper, “How to Detect Yips in

Golf”, was to identify sensitive methods for detecting the yips and evaluating

its aetiology. Forty subjects volunteered who were split into affected and non-affected

yips groups. All participants were right handed which standardises the results.

Both groups completed a psychometric testing battery by performing putting

sessions in the labs. Groups answered questions on their yips and golfing experience

by completing an online survey measuring trait anxiety, perfectionism, stress

coping strategies, somatic complaints and movement and decision reinvestment.

Testing was done on

putting performance over 5 different conditions that might trigger the yips.

These conditions include both arms, under pressure, one arm, with a uni-hockey

racket and with latex gloves. Results recorded using EMG of the arm,

kinaesthetic parameters, putting performance and situational anxiety. The

experiment took place in the lab on a putting surface 1.5m in length. There was

a monetary incentive - for every ball the subject earned 1 Euro. All Euros

earned would be donated to a charity in Africa

which would create high pressure as there was a need to hole the putts for a

worthy cause.

Statistical tests ran included

MANOVA’s (Multivariate Analyses Of Variance), Greenhouse Giesser correlation

applied and follow up analyses of variance (ANOVA). With this being said one

study concluded that yips causes the golfer to change their putter face due to

them being aware of having yips, not due to the situation (high or low pressure

etc.) (Marquardt 2009).

2.4 Links between

Papers

All three papers used monetary

incentives to create a higher pressure situation which would bring on yips and choking.

Limitations of these studies are they are all controlled and not in the natural

environment. There is no real competition or audiences with them which reduces

the effect of yips, choking and anxiety levels. Yips can be divided into two

categories (Type 1 and Type 2) which the papers agree upon, and that yips are

heavily influenced by experience, age, ability, and each individual’s

state/trait anxiety.

3.0 Summary

Reviewing all the papers,

there is no standardized method to identifying and/or quantifying yips affected

golfers. The paper, “How to Detect Yips in Golf”, (Klampfl,

Lobinger & Raab 2013, was the first of its kind to combine an array of

psychometric and psychophysiological, behavioural and kinematic measures, to build up a picture of what yips actually is and

how it can present itself. Its recommendations

for future research include kinematics to investigate more into yips and

possible interventions to eliminate them. “The Yips in Golf” paper concluded

with future research towards determining how stress (which golfers experience) interacts with the factors

underlying Type 1 (dystonia) and Type 2 (choking) yips. This study provides evidence

to support Smith’s model.

More studies can lead to

a classification for golfers with yips which could provide a useful framework

for the appropriate management of yips symptoms. In the “Self-Confidence and Performance”

paper, future research lent towards looking at the effects of anxiety and

self-confidence on performance rather than each of these relationships in

isolation and apply them to a range of sporting situations.

In conclusion, from all

the papers reviewed, future investigations of yips should use an array of tests

to increase the validity and reliability of understanding and identifying yips

before creating suitable interventions. For future research, more studies need

to be done on both yips, choking and self-doubt. Then, once more literature has

been gathered, and there is a better testing battery to identify yips, then

sports science can start to test for yips and choking, not only in golfers, but

in a range of sports.

References

1. Adler,

C. H., Crews, D., Hentz, J. G., Smith, A. M., & Caviness, J. N. (2005). Abnormal co-contraction in yips-affected but

not unaffected golfers: Evidence for focal dystonia. Neurology, 64,

1813–1814.

2. Adler,

C. H., Crews, D., Kahol, K., Santello, M., Noble, B., Hentz, J. G., et al

(2011). Are the yips a task-specific

dystonia or golfer’s cramp? Movement Disorders, 26, 1993–1996.

3. Baumeister,

R. F. (1984). Choking under

pressure—Self-consciousness and paradoxical effects of incentives on skilful

performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 610–620.

4. Bawden,

M., & Maynard, I. (2001). Towards an

understanding of the personal experience of the yips in cricketers. Journal

of Sports Sciences, 19, 937–953.

5. Eysenck, M. W., & Calvo, M. G. (1992). Anxiety and

performance: The processing efficiency theory. Cognition & Emotion, 6(6),

409-434

6. Feltz, D. L. (1988). Self-Confidence

and Sports Performance. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 16, 423-57.

7. Gucciardi,

D. F., Longbottom, J. L., Jackson, B., & Dimmock, J. A. (2010). Experienced golfers’ perspectives on choking

under pressure. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 32, 61–83.

8.

Hardy, L. (1990). A

catastrophe model of performance in sport.

9. Hardy,

L., & Fazey, J. (1988). The inverted-U hypothesis: A catastrophe

for sport psychology. University of Wales,

Bangor, SHAPE.

10. Hill, D.

M., Hanton, S., Fleming, S., & Matthews, N. (2009). A re-examination of choking in sport. European Journal of Sport

Science, 9, 203–212.

11. Klämpfl, M.

K., Lobinger, B. H., & Raab, M. (2013). How to detect the yips in golf. Human

movement science, 32(6), 1270-1287.

12. Lazarus, R.

S. (1974). Psychological stress and

coping in adaptation and illness. International Journal of Psychiatry in

Medicine, 5, 321–333.

13. Le Floch,

A., Vidailhet, M., Flamand-Rouviere, C., Grabli, D., Mayer, J. M., Gonce, M.,

et al (2010). Table tennis dystonia.

Movement Disorders, 25, 394–397.

14. Marqardt,

C. (2009). The Vicious circle involved in

the development of the yips. International Journal of Sports Science and

Coaching. 4, 67-88.

15. Masters, R.

S. W. (1992). Knowledge, nerves and

know-how: The role of explicit versus implicit knowledge in the breakdown of a

complex motor skill under pressure. British Journal of Psychology, 83,

343–358.

16. Mayer, F.,

Topka, H., Boose, A., Horstmann, T., & Dickhuth, H. H. (1999). Bilateral segmental dystonia in a

professional tennis player. Medicine & Science in Sports &

Exercise, 31, 1085–1087.

17. McDaniel,

K. D., Cummings, J. L., & Shain, S. (1989). The yips: A focal dystonia of golfers. Neurology, 39, 192–195.

18. Philippen,

P. B., Klämpfl, M. K., & Lobinger, B. H. (2012). Prevalence of the yips in golf across the entire skill range.

Manuscript submitted for publication.

19. Pont-Sunyer,

C., Martí, M. J., & Tolosa, E. (2010). Focal

limb dystonia. European Journal of Neurology, 17, 22–27.

20. Rosenkranz,

K., Butler, K., Williamon, A., Cordivari, C., Lees, A. J., & Rothwell, J.

C. (2008). Sensorimotor reorganization by

proprioceptive training in musician’s dystonia and writer’s cramp.

Neurology, 70, 304–315.

21. Rotheram,

M., Maynard, I., Thomas, O., & Bawden, M. (2007). To yip or not to yip, that is the question. Journal of Sports

Sciences, 25(Suppl. 2), S5–S6

22. Smith, A.

M., Malo, S. A., Laskowski, E. R., Sabick, M., Cooney, W. P. I. I. I., Finnie,

S. B., et al (2000). A multidisciplinary

study of the yips phenomenon in golf: An exploratory analysis. Sports

Medicine, 30, 423–437.

23. Smith, A.,

C. H. Alder, D. Crews (2003). The “yips”

in golf: a continuum between a focal dystonia and choking. Sports Med.

33:13-31.

24.

Smith, A.M., Alder,

C.H., Crews, D., Wharren, R. E., Laskowiski, E. R., Barnes, K. (2003). The Yips in Golf: A Continuum between a

focal dystonia and choking. Sports Medicine, 33, 13-31.

25. Stinear, C.

M., Coxon, J. P., Fleming, M. K., Lim, V. K., Prapavessis, H., & Byblow, W.

D. (2006). The yips in golf: Multimodal evidence

for two subtypes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 38,

1980–1989.

26. Woodman, T., & Hardy, L. (2003). The relative impact of cognitive anxiety and self-confidence upon sport

performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 21:443-457

27. Woodman,

T., Akehurst, S., Hardy, L., & Beattie, S. (2010). Self-confidence and performance: A little self-doubt helps. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(6),

467-470.

Andrew Richardson, Founder of Strength is Never a Weakness Blog

I have a BSc (Hons) in Applied Sport Science and a Merit in my MSc in Sport and Exercise Science and I passed my PGCE at Teesside University.

Now I will be commencing my PhD into "Investigating Sedentary Lifestyles of the Tees Valley" this October 2019.

I am employed by Teesside University Sport and WellBeing Department as a PT/Fitness Instructor.

My long term goal is to become a Sport Science and/or Sport and Exercise Lecturer. I am also keen to contribute to academia via continued research in a quest for new knowledge.

My most recent publications:

My passion is for Sport Science which has led to additional interests incorporating Sports Psychology, Body Dysmorphia, AAS, Doping and Strength and Conditioning.

Within these respective fields, I have a passion for Strength Training, Fitness Testing, Periodisation and Tapering.

I write for numerous websites across the UK and Ireland including my own blog Strength is Never a Weakness.

I had my own business for providing training plans for teams and athletes.

I was one of the Irish National Coaches for Powerlifting, and have attained two 3rd places at the first World University Championships,

in Belarus in July 2016.Feel free to email me or call me as I am always looking for the next challenge.

Contact details below;

Facebook: Andrew Richardson (search for)

Facebook Page: @StrengthisNeveraWeakness

Twitter: @arichie17

Instagram: @arichiepowerlifting

Snapchat: @andypowerlifter

Email: a.s.richardson@tees.ac.uk

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/andrew-richardson-b0039278

Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andrew_Richardson7

No comments:

Post a Comment