This article isn't a review of a theory or a training

method or even an interview with a coach or an athlete, as many of you are used

to. This is me having a go at my own field, my own subject, my own passion.

Sports Science and the fitness industry is a mess. In particular the route

towards coaching sport and elite level sport in the UK and Ireland.

It is the wild west of the job markets.

It may seem a bit hypocritical of me to be slagging off a

field I am trying to get into, but I am looking to teach not be an elite coach.

I don't like the job prospects based on the experience, already worked there

and the research I have done. I am happier teaching at a university, college

and or school PE/Sport Science.

The content of this article is based on an essay I just

wrote for my PGCE course, for the module Theory, Policy and Education. Where I

discuss the attractiveness of working in elite sport rather than moving your

focus to the Public Health sector where there is work and the skills of a Sport

Scientist can be transferable. Essay is based on UK markets as that is where my

current placements are and where I intend on working.

I was spurred onto move my report to the blog after I heard

the news from the Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU) and Connacht Rugby. They both

advertised internships which a high level of qualifications, long hours

and no salary. In short these advertisements were laughable and an

embarrassment to those who are working to get into the field. So much so they

were pulled down by both employers due to the backlash they received. I will

share the screenshots below and discuss.

Introduction and Aim

The aim of this report is to investigate the delivery of

Sport Science (SS) at Higher Education (HE) in the United Kingdom, and to shed

light on the lack of transparency within the SS field regarding its portrayal

in the media, university and by careers advisers. This will include looking at

how it is taught, comments by Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) for Higher

Education and rated by students. Further analysis will show statistics on

number of graduates per year and compare it to the current job market,

government targets and social issues that may impact the subject and the

public. The report will be making the majority of its

points and discussions referring to the article entitled “What can you do

with a sports science degree?” (THE,

2016) and to a few others to support its stance on the subject (AAAS, 2004; Foster,

2010; Doust, 2011).

- Link for original article: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/subjects/what-can-you-do-sports-science-degree

The aforementioned article discusses what skills, jobs, and

potential further study is available. It presents the field with the promise of

a good salary, employment and prospects. Yet it fails to be critical of the

subject and the layout of other options besides elite level sports jobs. It is

a Time Higher Education (THE) article and for its intended audience, it needed

to be short, snappy and easy to read. If it had a large amount of text

highlighting positives and negatives and heavy analysis, combined with

statistics, it would have put a lot of people off. Writing an article is very

different to writing a report. This is why when you read something in the news

compared to reading the actual report, it leaves out a lot of data and

potential for opinion swaying themes.

The other papers reviewed to support the original article, discuss

sports science in a very similar way, crucially leaving out any real critical

analysis and any opinions by current or former students. Coincidentally, and

conveniently, it shows nothing negative or undesirable that may cause someone

to stop reading and ponder their thoughts about the subject. Instead, it talks

as if it is all smooth sailing. This report will go into significant detail

about SS, to express what is really happening in the field alongside linking it

back with SS placements and continued personal professional development (CPPD).

(for context, the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) for

Higher Education is a review carried out every 6 years on each individual

university. So in the original essay I talked about my own university

(Teesside) rankings and ratings and added the ratings/rankings of its sports

courses as reviewed by the students. Neither QAA and or the Student survey

will be discussed in this article as it will have no significant bearing).

What is Sport Science?

SS can be defined as “a

discipline that studies how the human body works during exercise, and how sport

and physical activity promote health and performance from cellular to whole

body perspectives. The study of sports science traditionally incorporates areas

of physiology, psychology, biomechanics, and biokinetics” (TCUG,

2018; Wiki, 2018). SS was first taught in the UK in 1946 at the University of

Birmingham (UB) (UB, 2014). Currently, there are 154 Universities in the UK (REF2014,

2014; Wiki, 2017; England, 2018) as of 2017, 81 of which teach variations of SS

and/or SES (Guardian, 2018).

In the 2016/17 academic year, 10,165 SS students graduated (HESCU,

2017) from a HE establishment (Appendix 1.0). SS is taught through a variance

of delivery methods including (but not limited to); lectures, seminars,

practicals, lab work, conferences, presentations, essays, group work and poster

presentations. The professional standards and governing body of SS

accreditation in the UK is the British Association of Sport and Exercise

Scientists (BASES) (BASES, 2018). They provide all students, graduates and

members continued personal professional development (CPPD) to keep up with the

new and current scientific knowledge (BASES, 2018). SS, like many courses at university, is rated by the National

Student Survey (NSS) (Thestudentsurvey.com, 2018).

University and Higher Education (HE)

HE is defined by the Further and Higher Education Act

in 1992 (Legislation.gov.uk, 1992) as “any

UK University designated by Parliamentary Order, is eligible to receive funding

grants” (THE, 1997; Wiki, 2017). From 1980 to 2018, there has been a significant

increase of students across all university courses. In 1980, only 68,000 people

were starting university (Appendix 2.0). However, between 2015 and 2016

academic year, there was recorded 2.28 million students at HE (Universitiesuk.ac.uk,

2017). More recently, just this past September, over 500,000 started their

academic journey (Coughlan, 2017). One of the reasons for such a spike over the

years for student numbers at HE is student loans. The introduction of these

student loans (Blake, 2010) has made university more accessible to those that

would never have thought it possible (Appendix 2.0). “Poorer” students have

increased in numbers steadily over the years but there still remains a divide

between the wealthy and less well-off (Appendix 3.0).

Overall, this means more graduates, and

one could argue with the original article (THE, 2016), that by presenting

courses in such a positive light more students will go to university due to the

creation of these loans without realising other people will be doing the same

(leading to raising the standards for job requirements).

This is especially the case as the sports industry is one

of the fastest and highest earners in recent years. It was predicted in 2015

that by 2019 the industry would be worth 73.5 billion dollars (Heitner, 2015).

In hindsight, this was a fair estimate, but now looking at the market value,

this number has increased significantly to 90.9 billion dollars (Statista,

2014).

Sport Science (SS)

Graduate Prospects

A current SS or SES graduate would expect to go straight

into work or continue their education in the following sectors (as advertised

across a range of career sites); researcher (Jobs.ac.uk, 2018), lecturer (Prospectus.ac.uk,

2018a), PE teacher (NCS, 2018f), personal trainer (NCS, 2018g), gym instructor (NCS,

2018n), sports coach (NCS, 2018j), sports therapist (Prospectus.ac.uk, 2018b), sports

scientist (NCS, 2018m), sports physiotherapist (NCS, 2018L), sports

psychologist (NCS, 2018i), leisure centre manager (NCS, 2018e), lab technician

(NCS, 2018d), strength and conditioning coach (NSCA, 2016) and finally, a sports

journalist (Prospects.ac.uk, 2018c). If

one wanted to continue their education, they would usually do an MSc in SS or

SES, a PGCE (to go and teach in schools or colleges) (Appendix 1.0) and/or be

part of a research project to aim for a publication.

However, considering the job market in the UK, there are

very few jobs in the relevant degrees for these aspiring graduates. In fact,

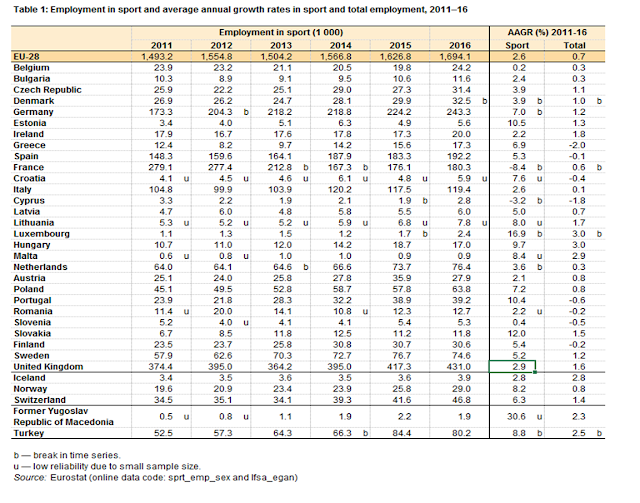

there is an oversaturation in the sports sector. In 2016 across the EU, there were

1.7 million people working in sports related jobs with 431,000 in the UK alone (Ec.europa.eu,

2018a) (Appendix 5.0). Since 2011 to 2016, the number of sports related jobs in

the UK has increased by 15.11% (Ec.europa.eu, 2018b) (Appendices 4.0 and 6.0)

which is good.

Interestingly though, out of the 431,000, only 32.8% are

employed with tertiary education (HE education) in the UK (Ec.europa.eu, 2018b)

(Appendix 8.0). Being in this sector, those with a higher education often find

themselves either having to study more to get the job they want. On the flip

side, graduates end up in a job they are “too qualified” for and generally

unrelated to their field.

Flaws with the Sports

Job Market

A common example is having a sports science degree yet only

working as a gym instructor. As the gym instructor role does not require a

university education, the qualification can be completed within a few weeks and

is very cheap (Ymcafit.org.uk, 2018). This is due to the Level 2 dictating the

industry from an insurance point of view (every gym must employ staff with this

qualification). With this knowledge, then why do a degree if you do not need

one to work in a gym? This is especially so when the statistics on the personal

training industry are not promising - in 2016, there were over 13,770

registered personal trainers in the UK, and out of that number, 58% felt they

have no job security. This is probably due to the fact that 80% of them are

self-employed and rely on supporting themselves rather having a fixed wage (Insure4Sport,

2016). Unfortunately in some cases, some aspiring students have had the

disappointing realisation that their dream career really cannot support them

financially.

An example of this is within the Strength and Conditioning (S&C)

strand of SS. The role requires a practitioner to understand a lot of different

sports, plan programmes, prevent injury and management and finally be able to

take and plan sessions per gender, age, weight, team and individual basis (English

Institute of Sport, 2018). This is a very skilled position and sought out role

within the sports industry. However, despite needing a lot of training,

financial investment and qualifications to become an S&C coach, the role

does not pay well and many of the positions are voluntary. As such, it is very

difficult to get a job that is financially viable.

The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA)

investigated their members who are in current employment. From 32,000 members,

fewer than 2,600 are employed at college/university level across the United

States of America (SS, 2018). In the UK, the United Kingdom Strength and

Conditioning Association (UKSCA) statistics show that of 47% of all their

members, half hold a Master’s degree or higher. Yet, 22% of these S&C

coaches are voluntary and disappointingly, a further 33% are paid less than

£19,999/year (SS, 2018). A couple of examples highlight this; Head of Sport

Science at Blackpool Football club was advertised with a starting salary of

£12,000 per year (Guru, 2017). From an article on the job, a poll was ran asking

fellow coaches whether UKSCA should have refused to advertise the job. Out of

380 respondents, 93% voted yes (Guru, 2017). The reason for such a majority

vote is because the advertised year’s salary would have barely covered a year

at HE and completing UKSCA accreditation training (Guru, 2017).

In another similar scenario, the Rochdale football club in

May 2017 advertised an Academy Sport Scientist (part time) on a salary of

£9,000, again requesting that candidates have a degree, relevant experience and

UKSCA accreditation (Rochdaleafc.co.uk, 2017). Just today (as posting this article), the Irish Ruby

Football Union (I.R.F.U) posted the following images and link on their twitter

feed offering a unpaid internship for sports science role.

Original Twitter

Link: https://www.trendsmap.com/twitter/tweet/987383807287455744

Shane Stapleton (author of original tweet) summed it

well with "Very disappointing that IRFU are looking for *unpaid*

40-hours-per-week, 6-month intern for a job that requires college

qualification. I note recent Examiner piece showing IRFU will receive two

cheques worth €300,000 from organisers EPCR for Munster and Leinster winning

ECC qfs" . Pictures below note the advertised job (will have to

zoom in or click and enlarge the images).

What made me shake my head was the fact they had the cheek

to ask for someone to work 40 hours a week unpaid but have a degree and maybe

have a MSc or PhD..........

Where was the logic in writing this advertisement. Then in

Irish Rugby again, Connacht advertised a position for a Intern Performance

Nutritionist 25-30 hours per week. UNPAID! How can someone justify a

position at a senior level sports team for both IRFU and Connacht to be working

30-40 hours a week for 6 months for no money. Needing a degree, further

postgraduate education and high skill sets in an array of modalities

to carry out an effective job. Makes the field look so stupid.

In the midst of all these

employment inconsistencies, a new initiative by the government is striving for

2 year degrees. The rationale for this is to reduce student costs in the long

term (BBC News, 2017). Yet what they fail to realise, is that degrees are 3 to

4 years duration to gain as much experience as possible to develop key skills

for employment. Reducing the time spent learning will de-skill the workforce thus

reducing the quality of the service provided. The Guardian newspaper even

discussed how this devalues education and is now turning universities into

profit machines rather than centres for learning and excellence (McDuff, 2017).

Other Graduate Jobs for

Sports Science Students

Despite this, many people go into SS with the vision to

work with elite sport, but end up disappointed. Teaching PE/Sport Science is usually one of these

avenues many students end up doing. This is not being detrimental to PE as a field. Many go into it and become excellent teachers, providing an excellent experience to their students. One of the reasons why I am doing a a teaching degree is so I can land myself job security in a field with little stability. I never came to university wanting to teach but now I want to do it.

The issue arises when graduates

realise that there are so few jobs, they end up looking for alternative jobs or further study. From

the 10,165 SS graduates in 2016/17, nearly 2,000 of them went straight back

into education either to do a MSc (47.7%) or a PGCE (31.5%) (Appendix 1.0) (HESCU,

2017). This highlights the point that a SS degree is not enough anymore to get

a job. You have to attain more qualifications to beat the rest of the

competition to ensure you are successful in the employability market of SS. This

can be backed up by Appendix 7.0 which shows the more you learn (and higher

level of education you attain), you expect a higher hourly wage. However, there

has to be jobs available first for this to be true.

Regardless of how this may seem, there are good prospects

for sports students if they were to shift their focus elsewhere from teaching

and elite level sport jobs. This is a factor that the THE 2016 article failed

to address and make students aware of (THE, 2016). There is an understaffed

sector needing the skill set which SS graduates have, and that is within the

Public Health realm (Gov.uk, 2018). Public Health covers the following jobs; Dietician

(NCS, 2018b), Mental Health support worker (Health Careers, 2018), Sports

Development Officer (NCS, 2018k), Drug and Alcohol Worker (NCS, 2018c), Data

Analyst (NCS, 2018a) and Physical Activity Coordinator (Jobhero.com, 2018). The

reason for these roles not being filled comes down to two main themes; (1) SS

is taught and marketed towards the elite and competitive side of sport, meaning

that general health, fitness and participation is ignored. (2) Health and

Social Care courses alongside business/managerial degrees, do not have many

people with the academic and practical skillset compared to someone with a SS

degree.

With this being the case, these jobs and students should be

steered towards each other. A bonus of these facilities is that many of them

offer in-house free CPPD training (CGl, 2018b). Change Grow Living (CGL)

provide their staff with in-house training for Naloxone administration (Appendix 8.0) which can save lives of those overdosing from opiates (2018c). An example

of this would be working for Public Health England (Gov.uk, 2018) or Change

Grow Living (CGL) (CGL, 2018a). CGL and Public Health England push for the

promotion of exercise as a form of prescription and rehabilitation based upon

the National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for their

clients (Nice.org.uk, 2014). This year in the Guardian newspaper (Pozniak, 2018), it is discussed and

suggested that exercise prescription is the way forward to combat this

country’s declining health.

How is SS Tackling

Public Health?

Dr Dale Esliger of Loughborough University, advocating for

the new MSc in Exercise as Medicine, talks about what his students would be

doing on this course; “Students won’t be

attending elite athletes beside the pitch, but rather looking at “prescribing”

exercise to the wider population, investigating the value of techniques such as

mindfulness, and researching how to deploy digital tools to motivate people to

exercise more. As a nation, we’re behind the likes of Australia in formalising

exercise advice within the health service. In the future we hope to see more

exercise professionals within the NHS. If we want clinicians to write exercise

rather than drug prescriptions, we need to give them the knowledge to do that” (Pozniak, 2018).

It is not just Loughborough University who have highlighted

this issue. Dr Kim Edwards of Nottingham University has shared her thoughts on

the matter as well; “There’s room in

the NHS for new roles, such as exercise instructors, that don’t

currently exist. However, though, it can feel poor in relation to the glamour

of treating soccer players by the pitch” (Pozniak, 2018).

United Kingdom’s Health

Crisis

These courses are emerging at universities due to some of

the major health issues facing the UK population; obesity (Ryan, 2018), heart

disease (Matthews-King, 2017) and mental health (Campbell, 2017). This is not

just a UK problem but a western civilisation issue. To borrow a phrase from the

film director Chris Bell; “Is there

really a war on drugs or are we a nation of prescription thugs?” (Youtube,

2016). This is referring to our culture seeking quick fixes rather than

lifestyle changes for a better quality of life, for example, take a few pills

to reduce your blood pressure rather than exercise. It is no coincidence that

with a reduction of PE in schools that obesity and mental health issues have

risen in school, college and university students (Rumsby, 2015;

Youthsporttrust.org, 2018).

Right now in the UK, there are 20 million adults, 39% of

total population, who are inactive (as of a report by the British Heart

Foundation) (BHF.org.uk, 2017). By simply increasing activity levels, obesity,

heart disease and mental health issues would be immensely countered. As

mentioned previously, this is mainly in the North of England (Appendix 9.0). Performing

exercise (or physical activity) greatly improves mental health and wellbeing as

evidenced by the Scottish Student Sport Research Report of 5000 students at HE

institutions compared to those that are not engaging with exercise or physical

activity (Precor.com, 2017) (Appendix 10.0).

Example Avenues of Work

for SS Graduates

Alternative placements/jobs within Public Health instead of

the standard coaching and SS roles include; Special population work (disabled,

special needs, ethnic groups etc.), training those with dual diagnosis (drug

and alcohol related issues), working in a needle exchange, providing exercise

advice to those who maybe using substances. Finally, exercise referral service

for those with mental or physical issues.

Summary

To conclude, the studied article THE, 2016, does not

portray an accurate representation of what SS is for the aspiring student.

However, it is not all doom and gloom for those who want to get into elite

sport. Just because the field is oversaturated does not mean you cannot

succeed. It simply means it may take longer, be more frustrating and require

higher (and additional) qualifications. Especially as the population increases,

more students will have access to university (Appendices 4.0 – 5.0) combined

with the popularity of sport growing. This may end up being more expensive in

the long run to get a job that you really want, especially as the popularity of

the field is not dying off anytime soon. If you have a passion for elite sport

and that is all you want to do, then no one can stop a student from achieving

their dream.

They should, however, be given a more honest review of the

job market and subject prospects, as well as real opinions from students,

tutors and employers so they can make their own decision. Another contributing

factor is the experience at university, facilitates offered, effort put in by

students, quality of the department and support of the tutors per module. These

factors play a huge role in the end result of a student’s degree and definitely

can impact on employability prospects.

All potential students, current scholars and recent

graduates should take a step back and look at their interest and subject from a

different perspective. They will realise there are more work opportunities for

them within the Public Health sector as identified in this report. These jobs

can provide a good income, reasonable hours, CPPD opportunities, progression

through a company and most importantly, work that is going to be impactful on

the local community and the nation itself. If more SS graduates took up roles

within Public Health, it would benefit local communities and the nation

greatly. This is evidenced by Sport England research whereby promoting sport,

reduces youths at risk of criminal behaviour and reoffending and lowers costs on

health care per person between £1,750 and £6,900 (Sportengland.org.uk, 2010)

annually.

Now I wish I had more time as I would like to go into the flaws and faults of;

- UKSCA

- PT qualifications

- Sports Therapy

- Course Content at Universities

But due to deadlines and other commitments I am unable to do so.

I hope you all enjoyed that and gives some light into what is happening within SS and the fitness industry.

Please share, like and subscribe to the page for more posts.

Thank you very much for reading

Kind regards

Andrew

References

1. BASES (2018). BASES - About Sport and Exercise Science. [online] Available at: http://www.bases.org.uk/About-Sport-and-Exercise-Science [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

2. Bases.org.uk. (2018). BASES - Job Vacancies. [online] Available at: http://www.bases.org.uk/Vacancies [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

3. BBC News. (2017). Two-year degrees to lower tuition fees. [online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-42268310 [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

4. Bhf.org.uk. (2017). Physical Inactivity Report 2017. [online] Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/physical-inactivity-report-2017 [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

5. Blake, H. (2010). Grants, loans and tuition fees: a timeline of how university funding has evolved. [online] Telegraph.co.uk. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews/8057871/Grants-loans-and-tuition-fees-a-timeline-of-how-university-funding-has-evolved.html [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

6. Campbell, D. (2017). NHS bosses warn of mental health crisis with long waits for treatment. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/jul/07/nhs-bosses-warn-of-mental-health-crisis-with-long-waits-for-treatment [Accessed 16 Apr. 2018].

7. CGL. (2018a). CGL | change, grow, live – health and social care charity. [online] Available at: https://www.changegrowlive.org/ [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

8. CGL. (2018b). Supporting you in your role. [online] Available at: https://www.changegrowlive.org/careers-volunteering/careers/supporting-you-in-your-role [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

9. CGL. (2018c). Naloxone: the opioid overdose reversal drug. [online] Available at: https://www.changegrowlive.org/get-help/advice-information/drugs-alcohol/naloxone-the-opioid-overdose-reversal-drug [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

10. Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). 2015. The English Indices of Deprivation 2015. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/465791/English_Indices_of_Deprivation_2015_-_Statistical_Release.pdf. [Accessed 20 February 2018]. P. 9

11. Doust, C. J. (2011). 'Sport and exercise science has become a driving force for change'. [online] The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/student/career-planning/sport-and-exercise-science-has-become-a-driving-force-for-change-2192287.html [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

12. Drennan, J. (2017). How do retired athletes find work? A footballer has set up a careers site to help. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/football/behind-the-lines/2017/sep/01/robbie-simpson-sport-careers-service-professional-footballer [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

13. Ec.europa.eu. (2018). Employment in sport - Statistics Explained. [online] Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Employment_in_sport [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

14. Ec.europa.eu. (2018b). [online] Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/a/aa/Employment_in_sport.xlsx [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

15. England, H. (2018). Home - Higher Education Funding Council for England. [online] Hefce.ac.uk. Available at: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/ [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

16. Foster, A. (2010). What to do with a degree in sports science. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/money/2010/dec/11/sports-science-degree [Accessed 10 Apr. 2018].

17. Gov.uk. (2016). Health matters: getting every adult active every day - GOV.UK. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-getting-every-adult-active-every-day/health-matters-getting-every-adult-active-every-day [Accessed 10 Apr. 2018].

18. Gov.uk. (2018). Public Health England - GOV.UK. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/public-health-england [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

19. Guardian. (2018). University league tables 2018. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/ng-interactive/2017/may/16/university-league-tables-2018 [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

20. Guru, T. (2017). Training Ground Guru | Blackpool's £12k Head of Sport Science job branded a 'disgrace'. [online] Training Ground Guru. Available at: https://trainingground.guru/articles/blackpools-12k-head-of-sport-science-job-branded-a-disgrace [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

21. Health Careers. (2018). Support, time and recovery worker. [online] Available at: https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/explore-roles/wider-healthcare-team/roles-wider-healthcare-team/clinical-support-staff/support-time-and-recovery-worker [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

22. Heitner. D. (2015). Sports Industry to Reach $73.5 Billion by 2019. [online] Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/darrenheitner/2015/10/19/sports-industry-to-reach-73-5-billion-by-2019/#1c6072001b4b [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

23. HESCU, (2017). [online] Available at: https://www.hecsu.ac.uk/assets/assets/documents/What_do_graduates_do_2017(1).pdf [Accessed 10 Apr. 2018].

24. Insure4Sport. (2016). Personal trainer statistics: 8 of the best – infographic. [online] Available at: https://www.insure4sport.co.uk/blog/personal-trainer-statistics-infographic/ [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

25. Jobhero.com. (2018). Activity Coordinator Job Description | JobHero. [online] Available at: http://www.jobhero.com/activity-coordinator-job-description/ [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

26. Jobs.ac.uk. (2018). Research Assistant (HE) - Careers Advice - jobs.ac.uk. [online] Available at: http://www.jobs.ac.uk/careers-advice/job-profiles/1793/research-assistant-he [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

27. Legislation.gov.uk. (1992). Further and Higher Education Act 1992. [online] Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1992/13/contents [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

28. Matthews-King, A. (2017). Obesity crisis could 'erode' health gains made from cutting heart attacks and strokes. [online] The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/obesity-crisis-britain-increase-strokes-heart-disease-lifespan-a8079006.html [Accessed 14 Apr. 2018].

29. McDuff, P. (2017). The two-year degree shows education has become just another commodity | Phil McDuff. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/dec/13/education-two-year-degree-commmodity [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

30. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018a). Data analyst-statistician | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/data-analyst-statistician [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

31. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018b). Dietitian | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/dietitian [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

32. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018c). Drug and alcohol worker | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/drug-and-alcohol-worker [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

33. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018d). Laboratory technician | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/laboratory-technician [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

34. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018e). Leisure centre manager | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/leisure-centre-manager [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

35. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018f). PE teacher | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/pe-teacher [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

36. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018g). Personal trainer | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/personal-trainer [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

37. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018h). Physiotherapist | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/physiotherapist [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

38. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018i). Sport and exercise psychologist | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/sport-and-exercise-psychologist [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

39. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018j). Sports coach | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/sports-coach [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

40. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018k). Sports development officer | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/sports-development-officer [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

41. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018L). Sports physiotherapist | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/sports-physiotherapist [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

42. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018m). Sports scientist | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/sports-scientist [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

43. Nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk. (2018n). Fitness instructor | Job profiles | National Careers Service. [online] Available at: https://nationalcareersservice.direct.gov.uk/job-profiles/fitness-instructor# [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

44. Nice.org.uk. (2014). Physical activity: exercise referral schemes | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. [online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph54 [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

45. NSCA. (2016). Becoming a Strength and Conditioning Coach. [online] Available at: https://www.nsca.com/education/articles/career-series/becoming-a-strength-and-conditioning-coach/ [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

46. Pozniak, Helena. (2018). How exercise prescriptions could change the NHS. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/mar/19/how-exercise-prescriptions-could-change-the-nhs?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Copy_to_clipboard [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

47. Precor.com. (2017). [online] Available at: https://www.precor.com/sites/default/files/brochures/55497%20Precor%20SSS%20&%20UKActive%20Report_HR.pdf [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

48. Prospects.ac.uk. (2017). What can I do with a sport science and coaching degree? | Prospects.ac.uk. [online] Available at: https://www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-do-with-my-degree/sport-science-and-coaching [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

49. Prospects.ac.uk. (2018a). Higher education lecturer job profile | Prospects.ac.uk. [online] Available at: https://www.prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/higher-education-lecturer [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

50. Prospects.ac.uk. (2018b). Sports therapist job profile | Prospects.ac.uk. [online] Available at: https://www.prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/sports-therapist [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

51. Prospects.ac.uk. (2018c). Newspaper journalist job profile | Prospects.ac.uk. [online] Available at: https://www.prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/newspaper-journalist [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

52. Qaa.ac.uk. (2016). Teesside University. [online] Available at: http://www.qaa.ac.uk/reviews-and-reports/provider?UKPRN=10007161#.WtfsXYjwaUk [Accessed 14 Apr. 2018].

53. Rochdaleafc.co.uk. (2017). Job Vacancy – Academy Sports Scientist (part-time) - News - Rochdale AFC. [online] Available at: https://www.rochdaleafc.co.uk/news/2017/may/job_academy_sportscientist/ [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

54. Rumsby, B. (2015). Alarming fall in school PE lessons casts doubt over government's commitment to tackling obesity crisis. [online] Telegraph.co.uk. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/othersports/schoolsports/11343801/Alarming-fall-in-school-PE-lessons-casts-doubt-over-governments-commitment-to-tackling-obesity-crisis.html [Accessed 15 Apr. 2018].

55. Ryan, V. (2018). Britain's obesity crisis is creating an 'unemployable underclass', says former Tory minister. [online] The Telegraph. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2018/01/16/britains-obesity-crisis-creating-unemployable-underclass-says/ [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

56. Science | AAAS. (2004). Finding the Right Track After Your Sports Science Degree. [online] Available at: http://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2004/07/finding-right-track-after-your-sports-science-degree [Accessed 10 Apr. 2018].

57. SS. (2018). Science for Sport (SS). [online] Available at: https://www.facebook.com/ScienceforSport/posts/2012416122105124 [Accessed 12 Apr. 2018].

58. Statista. (2014). Global sports market revenue 2005-2017 | Statistic. [online] Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/370560/worldwide-sports-market-revenue/ [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

59. Thecompleteuniversityguide (TCUG) (2018). Guide to Studying Sports Science. [online] Available at: https://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/courses/sports-science/guide-to-studying-sports-science/ [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

60. Thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk. (2018). Sports Science - Top UK University Subject Tables and Rankings 2018. [online] Available at: https://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/league-tables/rankings?s=Sports+Science [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

61. Times Higher Education (THE). (1997). The collision of two worlds. [online] Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/the-collision-of-two-worlds/104836.article?storyCode=104836§ioncode=26 [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

62. Times Higher Education (THE). (2016). What can you do with a sports science degree?. [online] Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/subjects/what-can-you-do-sports-science-degree [Accessed 10 Apr. 2018].

63. Times Higher Education (THE). (2017). National Student Survey 2017: overall satisfaction results. [online] Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/news/national-student-survey-2017-overall-satisfaction-results#survey-answer [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

64. UB (2014). Ranked first for Sport Science. [online] Available at: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/sport-exercise/news/2014/25sep-Ranked-first-for-Sport-Science.aspx [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

65. UKSCA, (2018). [online] Available at: https://www.uksca.org.uk/jobs [Accessed 11 Apr. 2018].

66. Universitiesuk.ac.uk. (2017). Students at higher education institutions by level and mode of study, 2015–16. [online] Available at: http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/facts-and-stats/data-and-analysis/Documents/patterns-and-trends-2017.pdf [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

67. University, T. (2018). Teesside University - About us - University statistics. [online] Tees.ac.uk. Available at: https://www.tees.ac.uk/sections/about/public_information/factsandfigures.cfm [Accessed 14 Apr. 2018].

68. Vanmeer, P. (2017). Health Unit now offering free drug overdose antidote in Lindsay | Kawartha 411. [online] Kawartha411.ca. Available at: https://www.kawartha411.ca/2017/08/30/health-unit-now-offering-free-drug-overdose-antidote-in-lindsay/ [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

69. Wiki. (2017). List of universities in England. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_universities_in_England [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

70. Wiki. (2018). Sports science. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sports_science [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

71. Ymcafit.org.uk. (2018). Certificate in Personal Training | YMCAfit. [online] Available at: http://www.ymcafit.org.uk/courses/certificate-personal-training [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

72. Youthsporttrust.org. (2018). [online] Available at: https://www.youthsporttrust.org/sites/yst/files/resources/documents/PE%20provision%20in%20secondary%20schools%202018%20-%20Survey%20Research%20Report.pdf [Accessed 10 Apr. 2018].

73. YouTube. (2016). Prescription Thugs Official Trailer 1 (2016) - Chris Bell Documentary

HD. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t5sWd00t-6g [Accessed 13 Apr. 2018].

Appendices

1. Graduate Sport Science data: HESCU, (2018) Page 46 (see reference list).

2. University Applications Rising: Coughlan. S. (2017) (see reference list)

3. Are Poorer Students less likely to go to University: Coughlan. S. (2017) (see reference list)

4. Employment in sport - Statistics Explained - European Commission (Ec.europa.eu, 2018a, see reference list)

5. Employment in sport - Statistics Explained - European Commission (Ec.europa.eu, 2018b, see reference list)

6. Employment in sport - Statistics Explained - European Commission (Ec.europa.eu, 2018b, see reference list)

7. Learn More = Earn More? : Coughlan. S. (2017) (see reference list)

8. Naloxone Kit: Vanmeer, 2017 (see reference list)

9. Inactive Adults across the UK (BHF.org.uk, 2017) (see reference list)

10. Scottish Student Sport Research Report (2016) (Precor.com, 2017) (see reference list)

Andrew Richardson, Founder of Strength is Never a Weakness Blog

I have a BSc (Hons) in Applied Sport Science and a Merit in my MSc in Sport and Exercise Science and I passed my PGCE at Teesside University.

Now I will be commencing my PhD into "Investigating Sedentary Lifestyles of the Tees Valley" this October 2019.

I am employed by Teesside University Sport and WellBeing Department as a PT/Fitness Instructor.

My long term goal is to become a Sport Science and/or Sport and Exercise Lecturer. I am also keen to contribute to academia via continued research in a quest for new knowledge.

My most recent publications:

My passion is for Sport Science which has led to additional interests incorporating Sports Psychology, Body Dysmorphia, AAS, Doping and Strength and Conditioning.

Within these respective fields, I have a passion for Strength Training, Fitness Testing, Periodisation and Tapering.

I write for numerous websites across the UK and Ireland including my own blog Strength is Never a Weakness.

I had my own business for providing training plans for teams and athletes.

I was one of the Irish National Coaches for Powerlifting, and have attained two 3rd places at the first World University Championships,

in Belarus in July 2016.Feel free to email me or call me as I am always looking for the next challenge.

Contact details below;

Facebook: Andrew Richardson (search for)

Facebook Page: @StrengthisNeveraWeakness

Twitter: @arichie17

Instagram: @arichiepowerlifting

Snapchat: @andypowerlifter

Email: a.s.richardson@tees.ac.uk

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/andrew-richardson-b0039278

Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andrew_Richardson7