I hope all is well and Happy New Year!

This is a the first post of 2020 and

the first guest article of the year!

We welcome Sophy Stonehouse, an elite

hockey player and student physiotherapist to run us through the training and

literature of this sport.

Hope all my readers you find this

useful :)

Enjoy!

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Training for a Female

Hockey Athlete

Field based team sports are characterised by the small periods of

high-intensity physical exertion interspersed by lower-intensity recovery

periods. Therefore, in such sports an athlete’s physical capability isn’t

limited by their VO2Max, aspects of physical performance such as muscular

power, change of direction speed, straight line running and repeated phases of

supramaximal exercise (Stolen et al, 2005; Buchheit, 2008; Rampinini et al,

2007).

Studies surrounding women’s field hockey have shown that roughly 20% of

the game included such high intensity performances (Limminck and Visscher,

2006); these efforts alone require a combination of endurance, strength, speed,

agility and skill. Depending on the athlete and level of competition, training

sessions may range from one session per week to two sessions each day, in which

stick and ball skills, weight training, endurance running and sprint training

may be involved. Playing at such standard is both physically and

psychologically demanding, in terms of the student athlete balancing both

academics and social interaction with training and match performances daily can

cause a further decline psychologically and physically.

Physiology

A game which involves semistochastic intermittent activity, maximal or

close to maximal anaerobic efforts, interspersed with submaximal aerobic phases

involving low to moderate intensity activity, with and without a ball over a

period of 70 minutes (Reilly & Borrie, 1992). Thus, field hockey is a

demanding sport that expects an individual to have the capability to combine

both aerobic and anaerobic ability while executing technical skill, such as

sprints, dribbling, passing, tackling and shooting, under pressure while being

fatigued mentally and physically (Spencer et al, 2005; Limmink & Visscher,

2006). Gabbett (2010) investigated the physiological demands of fourteen elite

Australian field hockey players during 32 league competitions and 19 training sessions

using GPS technology. During performance the average distance covered by a

performer is 6.6km, of which 97.3% was at low intensity (0-1m.s-1)

in comparison to physical exertion of sub maximal and maximal intensity (1-3

m.s-1 – 3-5m.s-1) although this data relates to the

demands of the sport, the research by GPS highlights inconsistency’s. Lidor and

Zav (2015) criticised GPS data analysis as it doesn’t represent the work rate

of athletes appropriately in relation to their individual capacity. Nevertheless,

from global positioning data it is identified that the proportion of high

intensity is small within competitive performance, repeated sprint ability

(RSA) is a key component of field hockey fitness (Spencer et al, 2004). RSA is

paramount for athlete success, being associated with key moments of play, such

as gaining advantage over an opposition player or generating a scoring

opportunity.

Benito et al (2016) expressed that the energy expenditure of the sport

is like that of Soccer and Lacrosse in the fact that performers are expected to

endure a combination of aerobic and anaerobic fitness measured at 30% and 70%

respectively. The speed at which hockey is performed leaves the potential that

a larger percentage of the game is more anaerobically demanding on the

performer, making speed an important characteristic and outlining that hockey

can be considered as an intermittent intensity sport producing fatigue (Gabbet,

2010). The duration of competitive match play puts a large amount of aerobic

strain on players and requires them to have a high level of energy expenditure

during competitive play. 17.5-30% of competition time is made up of high

intensity actives, such as sprinting, which are performed when the athlete has

direct involvement with the ball (Boyle et al, 1994; Reilly & Borrie,

1992). These periods of match play are also considered as critical to the

outcome of the game. Therefore, due to the multidirectional nature of this high

intensity sport, it is imperative for successful performance a field hockey

player should have the ability to change direction swiftly whilst maintaining

balance to assure there is no loss of speed. Highlighting that agility is an

essential physical component necessary for successful performance. (Lemmink,

Elferink-Gemser & Visscher, 2004)

The rapid and radical changes that field hockey has undergone within the

last decade, had a direct influence on the athlete competing, demanding a

highly developed aerobic and anaerobic energy system (Reilly and Borrie, 1992).

Within Elite field hockey female athletes, average heart rate has been measured

at 170 bpm (MacLeod et al, 2007), Lothian and Farrally (1992) found that female

players reportedly exercise during competitive game play with an energy

expenditure of 55.3 KJ.min-1. Whilst the sport may have a view of

being largely aerobic, the recovery periods at sub maximal intensities are

particularly brief. Various studies have investigated the contribution of

energy systems within field hockey, specifically during maximal sprint durations.

Typically, they have examined the metabolic responses from a player to maximal

efforts that range from 3-30s. When dissecting a sprint that has a 2-3s

duration, it is expressed that 55% of the energy is provided by PCr (Phospho

Creatine) , 32% for anaerobic glycolysis and 10% from ATP store (Spencer et al,

2005). A muscles concentration is measured to be large enough to sustain the

maximal intensity for a duration of around 6 seconds (Newsholme, 1986).

Psychology

Research that concerns psychology within team sports, shows there is a

greater focus on changes within athlete’s feelings and interpersonal relations

following winning, loosing and facing adversities such as injury (Podgórski,

2011). Physical activity can be affected by psychological factors but they may

also manifest and cause changes in biochemical parameters within the athlete’s

bloods through hormonal changes. Williams (1998) expressed that the development

of ‘psychological skill’ is a necessary component in the attainment of athletic

performance. Psychological demand is greater the higher the level of

performance the athlete attains due to successful psychological ability being

able to optimise performance as well as provide opportunity to develop the

athlete. (Abdullah et al, 2016). Bandura (1997) states the outside judgement of

a person’s capabilities to function at various performance levels affect the

individual’s choice of effort expenditures, persistence within tasks and choice

of activities. Field hockey players are exposed to many mental and emotional

challenges during 70 minuets of game play (Anders et al, 2008). The role of

psychological factors and skills in achieving optimal performance cannot be

underestimated (Van den Heever, 2006), identifying skills such as anxiety

management, motivation, mental preparation and self-confidence are paramount to

successful competition (Mahoney and Gabrie, 1987). O’Sullivan, Zuckerman and

Kraft (1997) present that basic optimistic self-confidence is advantageous and

an athlete being over-sensitive to criticism can often result in a decline in

performance. As a practitioner developing an understanding of your athlete will

allow you to develop an answer to the question of what sport psychological

skills discriminate better between successful and less successful performance

for your athlete (Kruger, 2010).

Training

Now you are fully equipped with the knowledge and understanding of the

demands of field hockey, when discussing how to train a female hockey field

hockey athlete, a topic that A. Richardson has already covered within the blog,

this is the foundation of what you build the program on (or any program for

success). This can be found within ‘Periodisation: A definitive guide by Andrew

Richardson’, specifically looking at the subheadings ‘3 Main Elements in a

Programme (regardless of sport) and ‘3 Phases of Any Programme for Long Term

Success’. Therefore, I would direct you to these articles to start. What I am

going onto express within this article is the key aspects of training for a

female, in conjunction with being a field hockey performer.

Training needs to be considered initially in relation to the

individual’s macrocycle. This is with the idea that, the performer needs to be

able to produce optimal performance for certain international periods. This can

be used to be further influence their micro cycle to assure optimal performance

is accessible for competing in club level hockey. This is due to the match

being typically scheduled at the end of a training week. Therefore, pre-season

usually focuses on the rebuilding of fitness in players following the off season.

With the aim to be that a maintenance of the specific capacities that has been

developed within preseason is focused on ‘in-season’.

1. The start of the journey, the

hypertrophy phase. The main aim of this phase is to increase the cross sectional

area of muscle and an increase in the storage capacity of high energy

substrates and enzymes, the length of this phase should be around 3-4 weeks,

but as you move through these phases volume should be increased as a the weeks

progress. Due to the nature of the sport we are training for and the fact that

we are not simply building muscle but generating an athletic performance

approach, we are focusing on changing the traditional bodybuilding method of

‘isolation exercises’ into ‘functional exercises’. Alongside this we will

accompany this phase of training with ‘aerobic capacity’

work, Hockey doesn’t require you to build size of your muscle but

this can be imperative for protection during the season as majority of injury

is the result of muscle imbalance. The focus will be lower body muscle dominant

due to the nature of the sport, as stated above the heavy reliance on power

output over short distances, however the incorporation of upper body shouldn’t

be ignored for endurance and skill reasons more so for those who are involved

in drag flicks or aerials as a distinctive skill.

Combining functional hypertrophy with aerobic capacity, will allow the

player to generate a bank of fitness, allowing the athlete to increase the

amount of work at a moderate pace for extended periods. During these work out

periods you will be aiming to develop a fuel efficiency (burning fat) and a

better endurance capacity, in relation to hockey think of this as the phases of

play when the balls been turned over and you’re doing defensive work to get

behind to regain possession.

Training Examples

(Functional Hypertrophy & Aerobic Capacity)

Functional

Hypertrophy (3-4 x per week)

- 1A. Back Squat 4 x 10-12

- 1B. CMJ 3 x 5

(2-3 mins rest between sets)

- 2 A. Banded Hip Flexor 4 x 15 (Each Leg)

- 2 B. Dumbbell Split Squat 4 x 10

(2-3 mins rest between sets)

- 3. Dumbbell Curl to press or Z-Bar 3 x 12

- 4. Hamstring Curls 3x12

- 5. Circuit of – dead bugs, banded rows and Russian twists

3x20

Aerobic Capacity (2-3

x per week)

This can be completed by running or biking.

- Long Distance moderate work 25-30 minutes @ 70% HR

OR

- 5 minuets at 70% HR, rest actively for 1 minute. X6

Once you’ve completed you functional hypertrophy session add your

aerobic session onto the end, be aware you may have an onset of delayed muscle

soreness (DOMS) the next day, do not be fearful this is your body telling you

its listening to the training. The hypertrophy sessions start with your

compound exercises, this is due to the correlative relationship to growth

hormone, getting the hormones released and circulating early. Remember to start

light and increase the weight how and when you feel stronger, when training I

like to note down my starting weight and increase by 2.5kg or 5kg depending on

the exercise. As a rule if you feel you could have completed 3-4 reps more of

an exercise, look at putting the weight up if your form lets you.

2 The strength and power phase, this is the training

related to converting what you’ve worked on within the first phase of

pre-season into your strength and power phase. It is a highly discussed topic

within field sports and can be alone important in gaining the correct physiological

make up for optimal performance. The phase aims to develop the fast twitch

nature of muscles. This looks at shifting training from volume to intensity.

Here we are going to split a 6 week period into 3 separate weeks to focus in on

what we are wanting to get out of training and to allow a progressive shift

from volume to intensity. This phase will also shift nicely into your in season

aspects.

This phase of training will be accompanied with anaerobic training, here

it’s time to tap into challenging your anaerobic system after the phase of

banking your aerobic capacity. This area of fitness is the athlete’s ability to

tolerate and remove lactic acid. Working within your anaerobic capacity will

make your body more efficient when oxygen uptake and conversion is at its

minimum. In relation to hockey, here we are focusing on that RSA aspect of the

sport, how you can still beat that defender when you have nothing left in your

tank.

The first 3 weeks will focus on strength, this is the maximum amount of

weight you can lift in a single repetition. As an athlete we are not here to

increase our strength base like a bodybuilder, we are lifting to increase force

production and power output (Power = Force x Distance over time) as increased

force production yields a larger power output when the time and distance are

directly proportional. The second 3 weeks is about maximising the athletes’

ability to use strength quickly, if you’re a high level athlete this will tend

to be your Olympic-style weight training as it requires you to move heavy

weights, quickly in a controlled manner.

Training Examples

(Strength, Power and Anaerobic Capacity)

Strength (3 weeks 3-4

x per week (60-70% IRM intermediate | 80%-100% 1RM Advanced))

- 1. Back Squat (or Olympic lift complex) 4 x 5-6

- 2. Dead Lift 4 x 5-6

- 3. Lat pull down – 4x 5-6

- 4. a jammer press – kneeling 4 x 5-6 each arm

- 4. b SA dumbbell row 4 x 5-6 each arm

- 5. Med ball throw rotation against wall 3 x 4-6

Recovery of 2-3 minuets in-between sets.

Power (3 weeks 3-4 x

per week (0-60% IRM lower body | 30-60% IRM Upper Body))

- 1a. Front Squat (power snatch) 6 x 3

- 1b. Box Jumps 6 x 3

(3 mins rest)

- 2 a. kneeling shoulder press SA DB 4 x5 each arm

- 2b. Face Pull cable 4x 10

- 3. Chest Press DB neutral grip 3 x 6

- 4. Adductor bench dips 3 x 8

- 5. Pallof Press 3 x 10 es

Anaerobic Capacity

2-3 x per week)

- Focus on power output 85% + HR: 6s on 60s off x 20 (5 mins rest after

10)

OR

- RSA stamina 80%+ HR : 60s on 60s off x 20 (5 mins rest after 10)

3. The hard work during these 2 phases

have paid off and it’s time to move into the peaking phase, this prepare the

athlete for international competition or to go into season performance. Within

the section we reduce the volume load again and increase the intensity within

the gym. The athlete will gain an obvious amount of volume through the on pitch

sessions, so we are just going to focus on the gym work, the aim of these

sessions is to reduce the negative impact that training has, maintaining the

physiological adaptions they have just created within preseason, creating an

optimal performance potential. This is not to suggest that the training gains

will just become non-existent as it’s highly recorded that performance gains

can be seen even during this phase of training. It is important to provide an

aspect of prehab (pre rehabilitation) within this section, allowing the athlete

to reduce its susceptibility to injury.

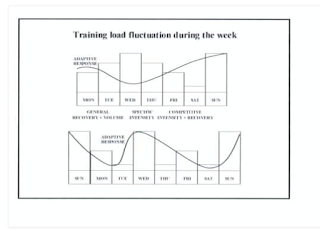

The typical load fluctuations during the week should aim for are shown

here in figure 1. From the Inigo Muiika book (Muijka

and Padilla, 2003). This is also discussed well within A. Richardson’s ‘What is

Tapering’ article, which I also sign post you too.

The typical load fluctuations during the week should aim for are shown

here in figure 1. From the Inigo Muiika book (Muijka

and Padilla, 2003). This is also discussed well within A. Richardson’s ‘What is

Tapering’ article, which I also sign post you too.

For the athletes time in the gym, it’s time to sit

down and discuss the goals they have within the season, after creating a

brilliant bank of hockey related fitness in preseason during a training week I

would aim training around pre-habiliation and the small margins of improvement

that are specific to the athlete. For the female athlete they are susceptible

to ACL injury at an alarmingly higher rate, the risk factors are anatomical,

environmental, hormonal and biomechanical (Orthop, 2016). At risk situation for

ACL injuries is during non-contact, which can be worked on during these

sessions, appear to be deceleration, cutting or changing direction and landing

(Griffin, 2001). Therefore, simple incorporation of these into a

dynamic warm up, pre gym and field session can drastically reduce your

athlete’s risk of a career threatening injury.

Example

of warm up:

Example of In season gym training:

This is a block of my own in season training, this

is an example and shouldn’t be followed lightly. I complete 2 conditioning

sessions a week during the week that doesn’t affect my weekend performance,

with the idea that through training on pitch 3 x a week I am hitting intensity,

however if I am looking to do extra I focus on the anaerobic sessions that were

stated above in preseason phase 2. My in season goals are power (velocity) and

a maintenance of whole body fitness.

It is important to note that this session takes

myself no longer than an hour, and introducing intensity into each movement

allows this session to leave me feeling worked. It is important to note that

keeping the gym a safe place is paramount when following any training regime

and also allowing adequate recovery time between sessions whether that is

within a double training day or days between sessions is imperative for

success. Alongside this, training before a performance day should also be

monitored. I would highly recommend generating a training load excel sheet,

these are not complicate to generate and can be found on YouTube, feel free to

contact myself if you’re struggling with this.

Conclusion

After being exposed to many variations of training

throughout my years within sport, both hockey and football. My hope is that you

find this article as insightful as I found putting my ideas down on paper. The

findings I have displayed are ones of personal preference which have resulted

in achieving my own goals, further research should be completed into individual

athletes and what works for them, as we are all different. I believe that if

you are looking to improve your or an athletes performance it is key to follow

a blueprint to ensure you are training the fundamental aspects of the sport you

are playing. I would like to thank D. Green for his knowledge and help with

this article and A. Richardson for giving me a platform to write about

something I am extremely passionate about.

Author Details

My name is Sophy Stonehouse, I am an elite level

athlete. Within field hockey I have been part of the English hockey player

system from 14 to 18, competing at county and national level, currently playing

in BUCS south prem B at Kings College University. I also play Football, having

played for England CYP u17s, Teesside centre of excellence, Durham WFC,

Middlesbrough Ladies FC and Sunderland Ladies AFC. I have a 1st Class

BSc in (Applied) Sport Science from Teesside University and I am currently

studying an MSc in Physiotherapy (pre-reg) at Kings College University London.

At both institutions I have been privileged to be on the Elite Athletic Scholar

programs where I have been conditioned by some of the best minds in the field.

Contact Information;

- Sophy Stonehouse BSc, MCSP.

- Email: sophy.stonehouse@kcl.ac.uk

- Contact Number – 07557963734

References:

- Abdullah, M. Musa, R. Maliki, A. Musawi, H.Maliki, B. Kosni, N. & K. Suppiah, Pathmanathan.

(2016).‘Original Article Role of psychological factors on the performance

of elite soccer players’. Journal of Sport Science, 16. pp.170-176.

- Anders,

E., Myers, S. & Myers, S. (2008). Field Hockey: Steps to Success (2nd

ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers.

- Bandura,

A. (1990). ‘Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of personal

agency’. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 2,

128-163.

- Butlet, R. & Hardy, L. (1992) ‘The performance profile: Theory

and application’. Journal of Sport Psychology. 6, pp.253-264.

- Dawson,

B. Fitzsimons, M. & Ward, D. (1993) ‘The relationship of repeated

sprint ability to aerobic power and performance measures of anaerobic

capacity and power’. Journal of Science and Medicine in

sport, 25, pp88-93.

- Elferink-Gemser, M. Visscher, C. Van Duijin,

M. & Lemmink, K. (2006) ‘Development of the interval endurance

capacity in elite and sub-elite youth field hockey players’. British

Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(4), pp.340-345.

- Gabbett,

T. Jenkins, D. & Abernethy, B. (2009) ‘Game-Based training for

improving skill and physical fitness in team sport athletes’. International

journal of Sport Science & Coaching, 4(2), pp.273-283.

- Gould,

D. Dieffenbach, K. & Moffett, A. (2002) ‘Psychological characteristics

and their development in Olympic champions’. Journal of Applied

Sport Psychology, 14, pp. 172-204.

- Griffin, L.Y. ed., 2001. Prevention of noncontact ACL injuries. Amer Academy of Orthopaedic.

- Kruger, A. (2010). ‘Sport psychological skills that discriminate

between successful and less successful female university field hockey

players’. African Journal for Physical, Health Education,

Recreation and Dance, 16 (2), pp. 240-250.

- Leslie, V. 2012. Physiological and match performance

characteristics of field hockey players (Doctoral dissertation,

Loughborough University).

- Lidor, R. & Ziv, G. (2015) ‘On-field

performances of female and male field hockey players- a review’. Journal

of Sport Science, 15, pp. 20-38.

- Limmink, K. & Visscher,

S. (2006) ‘Role of energy systems in two intermittent field

test in women field hockey players’. Journal of Strength and

Conditioning Research. 20(3), 682-688.

- Lothian

F. and Farrally M. (1992) ‘Estimating the energy cost of women’s hockey

using heart rate and video analysis’. Journal of Human Movement Studies,

23, pp. 215-231

- Mahoney,

M.J. & Gabrie, T.J. (1987). ‘Psychological skills and exceptional

athletic performance’. Journal of Sport Psychology, 1, pp. 140-199.

- O’Sullivan,

D . Zuckerman, Z. & Kraft, M. (1997). ‘Personality characteristics of

male and female participants in team sports’. Journal of

Personality and Individual Differences, 25(1), pp.119-128.

- Orthop, J. (2016) ‘ The female ACL: why is it more prone to injury’

journal of orthopaedics, 13(2).

- Reilly,

T. & Borrie, A. (1992) ‘Physiology applied to field

hockey’. Journal of sport medicine, 14(1), pp.10-26.

- Shete,

A. Bute, S. & Deshmukh, P. (2014) ‘A study of VO2 Max and body fat

percentage in female athetles’. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic

Research, 8(12).

- Spencer, M. Bishop, D. & Lawrence, S.

(2004) ‘Longitudinal assessment of the effects of field hockey training on

repeated sprint ability’. Journal of science and medicine in

sport, 7(3), pp.323-334.

- Spencer,

M. Bishop, D. Dawson, B. & Goodman, C. (2005) ‘Physiological and

metabolic responses of repeated-sprint activities: specific to field based

team sports’. Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(12),

pp.1025-1044.

- Spencer, M. Lawrence, S. & Rechichi, C. (2002)

‘Time-motion analysis of elite field hockey’. Journal of sport

science medicine, 5(4), pp. 102.

- Spielberger,

C. Gorsuch, R. & Lushene, R. (1970) ‘Manual for the

state-trait anxiety inventory’. Palo Alto: Consulting

Psychologists Press.

- Stolen,

T. Chamari, K. Castagna, C. & Wisloff, U. (2005). ‘Physiology

of Soccer’. Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(6), pp.501-356.

- T. Gabbet (2010) ‘GPS analysis of elite

women’s field hockey training and competition’. The Journal of

Strength & Conditioning Research. 24(5), pp.1321-1324.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thank you Sophy for a fantastic article all about Female Hockey! I am sure all of the readers will agree, this is a great way to kick off the blog for 2020 with such a detailed piece of work.

Thank you for your contribution

Thank you to all our readers!

Have a great 2020!

Kind regards

Team "Strength is Never a Weakness"

Andrew Richardson, Founder of Strength is Never a Weakness Blog

I have a BSc (Hons) in Applied Sport Science and a Merit in my MSc in Sport and Exercise Science and I passed my PGCE at Teesside University.

Now I will be commencing my PhD into "Investigating Sedentary Lifestyles of the Tees Valley" this October 2019.

I am employed by Teesside University Sport and WellBeing Department as a PT/Fitness Instructor.

My long term goal is to become a Sport Science and/or Sport and Exercise Lecturer. I am also keen to contribute to academia via continued research in a quest for new knowledge.

My most recent publications:

My passion is for Sport Science which has led to additional interests incorporating Sports Psychology, Body Dysmorphia, AAS, Doping and Strength and Conditioning.

Within these respective fields, I have a passion for Strength Training, Fitness Testing, Periodisation and Tapering.

I write for numerous websites across the UK and Ireland including my own blog Strength is Never a Weakness.

I had my own business for providing training plans for teams and athletes.

I was one of the Irish National Coaches for Powerlifting, and have attained two 3rd places at the first World University Championships,

in Belarus in July 2016.Feel free to email me or call me as I am always looking for the next challenge.

Contact details below;

Facebook: Andrew Richardson (search for)

Facebook Page: @StrengthisNeveraWeakness

Twitter: @arichie17

Instagram: @arichiepowerlifting

Snapchat: @andypowerlifter

Email: a.s.richardson@tees.ac.uk

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/andrew-richardson-b0039278

Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andrew_Richardson7